“Les trois grands groupes qui souhaitent amener ce pays à la guerre sont les Britanniques, les Juifs et l’administration Roosevelt. » Charles Lindbergh, discours à Des Moines Septembre 1941

Au début de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, Charles Lindbergh, célèbre aviateur et explorateur américain, devint le porte-parole du mouvement anti-guerre America First Committee. “L’aigle solitaire” devint l’une de ses figures les plus connues. Ecouté par des millions de personnes, face à des foules immenses, Lindbergh lisait ses discours au Madison Square Garden à New York ou au Soldier Field à Chicago.

Crée en Septembre 1940, America First Committee n’était pas seulement un groupe anti guerre mais refusait également toute aide humanitaire. Son programme était simple. Depuis que les Etats-Unis, même préparés à la guerre et prêts à riposter contre une attaque allemande ou japonaise, il n’y avait aucune raison de soutenir l’Angleterre. Beaucoup avaient également rejoint America First Committee pour attaquer le Président Roosevelt et sa politique du New Deal alors que d’autres activistes au sein du même mouvement étaient pacifistes dont le candidat socialiste aux présidentielles Norman Thomas. Bien qu’a nti-fasciste, son parti n’arrivait pas à convaincre comment vaincre le fascisme sans s’engager dans la guerre. D’autres étaient entrés à America First Committee pour d’obscures raisons avec des sentiments xénophobes, anti-sémites et anglophobes. Les interventionistes juifs ne pouvaient être, selon eux, motivés que par l’envie d’aider leurs coreligionnaires d’Europe. Pour les sauver, les Juifs seraient alors prêts à sacrifier des vies américaines (pensée plus forte dans les familles conservatrices du Sud et du Sud-Ouest des Etats-Unis où la population juive était peu importante).

nti-fasciste, son parti n’arrivait pas à convaincre comment vaincre le fascisme sans s’engager dans la guerre. D’autres étaient entrés à America First Committee pour d’obscures raisons avec des sentiments xénophobes, anti-sémites et anglophobes. Les interventionistes juifs ne pouvaient être, selon eux, motivés que par l’envie d’aider leurs coreligionnaires d’Europe. Pour les sauver, les Juifs seraient alors prêts à sacrifier des vies américaines (pensée plus forte dans les familles conservatrices du Sud et du Sud-Ouest des Etats-Unis où la population juive était peu importante).

Même si les églises montraient beaucoup moins de pacifisme qu’en 1914, les témoins de Jéhovah restaient ceux qui refusaient toute participation à quelconque service militaire et des milliers de jeunes hommes qui ont refusé de porter les armes ont été jetés en prison.

Les communistes américains, opposés à la guerre jusqu’en juin 1941, finalement prennent pas à l’effort de guerre et tentent même d’en prendre le contact. Après l’attaque d’Hitler en Union Soviétique, ils changent de position et accusent l’America First Committee comme une cellule nazie.

Beaucoup d’isolationnistes étaient originaires du Midwest, une région peu sensible aux problématiques européennes. D’autres étaient fermement pro-allemands. Certains étaient originaires d’Allemagne et restaient attachés à leurs racines malgré le régime nazi.

Dans les années 30, l’opinion américaine était largement en faveur de rester à l’écart de tout conflit malgré les événements de pogroms anti-juifs et l’occupation d’une partie de la  Tchécoslovaquie. “Non personne se sentant humaniste ne peut condamner la persécution de la race juive en Allemagne” déclare Lindbergh. L’aviateur n’était pas contre la guerre mais pas celle contre les Nazis.

Tchécoslovaquie. “Non personne se sentant humaniste ne peut condamner la persécution de la race juive en Allemagne” déclare Lindbergh. L’aviateur n’était pas contre la guerre mais pas celle contre les Nazis.

Beaucoup aussi croyaient, d’après John Flynn, que Roosevelt voulait la guerre afin de trouver “une glorieuse échappatoire aux problèmes internes de l’Amérique”. The Chicago Tribune assurait à ses lecteurs qu’une guerre couterait “400 millions de milliards de dollars, un million de morts et plusieurs millions de vies ruinées. »

Les opinions changèrent au printemps 1944 avec la défaite de la France. L’Angleterre se retrouvait alors seule face à l’Allemagne. Un plus grand nombre d’Américains imaginaient qu’Hitler pouvait ensuite les attaquer. Ils souhaitaient alors que la Grande Bretagne ne perde pas la guerre. Certains Américains étaient également prêts à s’engager au combat et se sont engagés dans les troupes finlandaises, norvégiennes ou britanniques. D’autres voulaient au moins faire quelque chose pour l’Europe. Felix, jeune garçon du Massachussetts, s’est alors engagé dans l’armée américaine dans l’espoir de libérer la Bretagne, la terre de ses parents.

En 1940, le Congrès vota la première législation en temps de paix. Souhaité par les militaires, l’enrôlement militaire devait passer à partir de 18 ans mais fut refusé par l’opinion publique. Les minorités ethniques furent mobilisées au même taux que les blancs avec le même salaires même si les noirs restaient dans des unités uniquement noires.

L’avis des Américains changea peu à peu et les mois précédents Pearl Harbor furent des moments difficiles pour America First. Roosevelt commença à envoyer de l’aide aux Britanniques et aux Soviétiques ce que le Congrès autorisa rapidement.

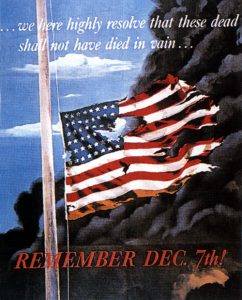

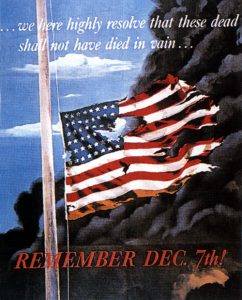

Hugh de Californie, volontaire pour les gardes nuits qui surveillait le ciel contre toute menace  de l’aviation allemande, était oppose à la guerre jusqu’au “jour de l’infamie”. Le dimanche 7 décembre 1941, Pearl Harbor fut bombardé par le Japon. Hugh participait à un meeting de charité pour les zones de guerre.

de l’aviation allemande, était oppose à la guerre jusqu’au “jour de l’infamie”. Le dimanche 7 décembre 1941, Pearl Harbor fut bombardé par le Japon. Hugh participait à un meeting de charité pour les zones de guerre.

“Lorsque nous sommes sortis du meeting, nous avons appris la nouvelle de l’attaque. Nous sommes alors retournés au meeting et nous avons augmenté nos donations. Avant je pensais que chacun devait régler ses propres problèmes. Puis, j’ai finalement réalisé que la situation avait radicalement changé ». En tant que soldat spécialiste de la montagne, Hugh fut envoyé en Europe à la fin de l’année 1944.

Même durant la guerre, Stanley, un artilleur new-yorkais ne voyait de raison à la guerre pour les Américains puis avec son unité, il découvrit le camp de concentration de Dachau. A ce moment-là, en avril 1945, il réalisa pourquoi les Américains s’étaient finalement engagés.

America First: Isolationism in the U.S. during the Second World war

“The three most important groups who have been pressing this country toward war are the British, the Jewish and the Roosevelt administration.” Charles Lindbergh- Des Moines Speech- September 1941

At the beginning of the Second World War, Charles Lindbergh, the world-famous aviator and explorer, became spokesman of the antiwar America First Committee. The lone eagle soon became its most prominent public spokesman. Heard by millions, his speeches were given to Madison Square Garden in New York City and Soldier Field in Chicago to overflowing crowds.

Created in September 1940, the America First Committee, was not only against entry into the war. It also opposed aid. Its program was simple. Since the United States, if properly armed, was impregnable against German or Japanese attack, there was no reason to help  England. Many joined the AFC as a way of attacking President Roosevelt and the New Deal. Some antiwar activists were pacifists including Socialist Party presidential candidate Norman Thomas. Although anti-fascist, his Party had never been able to explain how fascism could be eliminated without war. Still others had even more sinister reasons. It revealed xenophobic, anti-Semitic and Anglophobic sentiments. Jewish interventionists could therefore be motivated only by a desire to help co-religionists in Europe. To save them, Jews appeared willing to sacrifice American lives (It was strongest in the traditionally conservative south and southwest, areas of small Jewish population).

England. Many joined the AFC as a way of attacking President Roosevelt and the New Deal. Some antiwar activists were pacifists including Socialist Party presidential candidate Norman Thomas. Although anti-fascist, his Party had never been able to explain how fascism could be eliminated without war. Still others had even more sinister reasons. It revealed xenophobic, anti-Semitic and Anglophobic sentiments. Jewish interventionists could therefore be motivated only by a desire to help co-religionists in Europe. To save them, Jews appeared willing to sacrifice American lives (It was strongest in the traditionally conservative south and southwest, areas of small Jewish population).

Though, the churches showed much less pacifism than in 1914, the Jehovah Witness denomination, however, refused to participate in any forms of service, and thousands of its young men refused to register and went to prison.

American communists were antiwar until June 1941 and tried to infiltrate or take it over. After Hitler attacked the Soviet Union, they reversed positions and denounced the America First Committee as a Nazi front.

Many isolationists also came from the Midwest, an area never as sensitive to European problems. Still others were covertly pro-German. Some were German-Americans whose sentimental attachments had not been diminished by the crimes of the Nazi regime.

By the 1930’s, Opinion in the United States was overwhelmingly in favor of staying out of the war in spite of the anti-Jewish pogroms and the occupation of the Czech lands. It was  consistently minimized or ignored. « No person with a sense of the dignity of mankind can condone the persecution of the Jewish race in Germany. » Lindbergh declared. He was not against war. The aviator simply opposed war with the Nazis.

consistently minimized or ignored. « No person with a sense of the dignity of mankind can condone the persecution of the Jewish race in Germany. » Lindbergh declared. He was not against war. The aviator simply opposed war with the Nazis.

Many also believed, in the words of John Flynn, that Roosevelt wanted war because he found it a “glorious, magnificent escape from all the insoluble problems of America.” The Chicago Tribune assured readers it would cost “four hundred billion dollars, a million deaths, and several million ruined lives.”

Assumptions about the course of the war changed in the spring of 1940 with the fall of France. It left England to face Germany alone. An even larger number of Americans as a result came to believe Hitler would eventually attack them. They were more anxious than ever to make sure Britain would not lose. Some Americans were also ready to fight. A few joined allied troops in Finland, Norway or Britain. Some people really wanted to do something for Europe. For instance, Felix, a young man from Massachusetts, went into the Army to liberate Brittany, his parents’ homeland.

In 1940, Congress passed the first peace-time draft legislation. The drafting of 18-year olds was desired by the military but vetoed by public opinion. Racial minorities were drafted at the same rate as Whites, and were paid the same, but blacks were kept in all-black units.

The public mood was changing and the last months before Pearl Harbor were disappointing for America First. Roosevelt started to send helps to the British and Soviets and Congress quickly approved.

Hugh from California, volunteer to stand night watches listening for German aircraft, like  most Americans, still refused to go to war till “the day of infamy”. On Sunday, December 7, 1941 when Pearl Harbor was bombed by Japan, Hugh was in a meeting with a group that was doing charitable work in the war torn areas

most Americans, still refused to go to war till “the day of infamy”. On Sunday, December 7, 1941 when Pearl Harbor was bombed by Japan, Hugh was in a meeting with a group that was doing charitable work in the war torn areas

“When we came out of that meeting we learned of the bombing. We went right back into the meeting and changed a number of our contributions for help. Before that I had thought it was other peoples’ war and we should let them solve their problems. Then my eyes and understanding of the situation changed dramatically”. As a 10th Mountain Division soldier, Hugh was sent to Europe in late 1944.

Even during the war, Stanley, a New York artilleryman, didn’t find a reason to be at war until he discovered with his unit the infamous Dachau concentration camp. At this time, in April 1945, he realized why the Americans were fighting.