.

.

.

aussi un photographe qui couvrait la guerre?

.

.

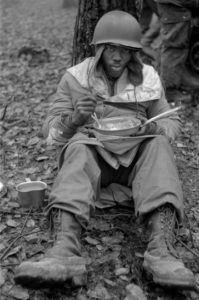

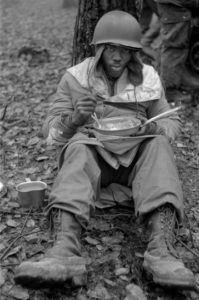

J’étais d’abord un soldat puis un photographe. J’avais un appareil photo et avec chance, dans toutes les villes où nous passions, je pouvais obtenir de la pellicule. L’armée m’en a également donné. La Normandie a été une exception. Tout avait été détruit et

c’était impossible de trouver un magasin de photos ouvert. Un jour, je suis arrivé devant un de ces commerces en ruines. J’ai fouillé les décombres et j’ai trouvé des produits chimiques conçus pour traiter les films négatifs. J’ai mélangé le tout dans un récipient avec mon doigt. La nuit, j’ai développé 10 pellicules dans 4 casques de soldats. J’ai séché les films sur les branches d’un arbre. La seule lumière que j’avais c’était la lune. Le matin suivant, j’ai regardé les négatifs des photos. Ils étaient parfaits.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Les Français étaient très heureux d’être mes modèles. Ils nous embrassaient et nous disaient: « Merci », « C’est très bien » [en français dans le texte]. Les libérer des Allemands

était comme leur offrir un cadeau. Une femme à Mont-Dol (Ille-et-Vilaine) s’est précipitée sur les soldats et a donné son fils à l’un d’entre nous, le Première classe Logfren. J’ai pris la photo de ce moment.

Lorsqu’une mère met son fils dans les bras d’un inconnu – cela montre qu’elle donne toute sa confiance. Je suis persuadé que cette femme ne l’aurait pas fait avec un soldat allemand. C’est triste car Logfren a été, des mois plus tard, porté disparu durant la bataille des Ardennes. Il a probablement été tué. En tant que photographe, je savais que j’accomplissais une tâche particulière. En général, l’armée envoyait des photographes attitrés mais il n’y avait personne là où nous passions. J’ai donc décidé de couvrir tous les moments que nous vivions. Durant la Première Guerre mondiale, il n’y avait pas de photographes sur le front ou dans les villes avoisinantes. Les appareils étaient trop lourds à déplacer donc les autorités ne s’en souciaient pas. Au début de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, l’armée américaine ne s’était pas non plus préoccupée d’avoir des appareils photos parmi les troupes. Au sein de la 83ème Division d’Infanterie, il n’y avait que 15 appareils photos. Certains soldats avaient le leur également. Cependant, les photos n’étaient pas bonnes. J’avais appris avant la guerre à être un bon photographe donc je savais quoi faire. Mes photos m’ont permis de travailler ensuite pour des journaux tels que Flair magazine et Look. Lorsque la guerre de Corée a commencé en 1950, l’armée américaine a interdit les appareils photos. J’ai eu par conséquent la chance d’avoir pu être autorisé à prendre des photos durant la guerre.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Un jour, en Normandie, un interprète connaissant le français, n’arrivait pas à comprendre un fermier. Je suis arrivé et j’ai compris que cet homme parlait en fait le molisan, le dialecte de la Molise, ma région d’origine en Italie. Je comprenais ce qu’il disait. C’était en fait un prisonnier italien vivant en France. Je n’ai rien dit à mes officiers car il aurait eu des problèmes.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Oui nous l’avons fait. C’était en pleine bataille des Ardennes. Au milieu de la forêt, nous avons décoré un sapin et j’ai pris la photo. Malgré les moments difficiles, nous arrivions à avoir de bons moments ensemble.

J’ai en effet pris beaucoup de photos de morts américains et allemands. Je l’ai fait parce que je voulais que l’on comprenne que la guerre n’est pas un jeu. Il n’y a pas de bons allemands, de bons français ou de bons américains. Il n’y a que des êtres humains. Durant la bataille des Ardennes, j’ai dû être de garde toute la nuit devant notre quartier général. Ce fut nouveau pour moi car en général, les officiers choisissaient des gars costauds pour une telle mission. A 2 heures du matin, j’ai entendu des bruits de pas dans la neige. J’ai crié : « Qui va là ? ». C’était le sergent Harry E. Shoemaker (F Company, 331st Infantry). Je savais que quelque chose de grave était arrivé. Un sergent ne peut pas quitter son peloton. Shoemaker était l’unique survivant. Il m’a emmené sur les lieux du combat. J’ai vu tous les cadavres dans la neige. Les Allemands avaient tué tous nos soldats à la mitrailleuse et

un tank Tigre avait détruit nos chars. C’était une vision de désolation. Shoemaker m’a raconté avoir été témoin d’une scène : un soldat allemand, en uniforme blanc, avait tiré avec son pistolet sur 27 corps américains afin de les achever. J’ai vu un de ces cadavres couverts de neige. Le soldat avait l’air si calme. Quand j’ai pris la photo c’était comme un requiem. La mort est l’aspect le plus affreux de la vie. Sur cette photo, elle est pourtant belle. Quelle contradiction ! Lorsque vous êtes artiste, vous devez mettre de côté vos sentiments. Vous devez devenir un salopard au cœur froid. Je voulais faire une photo d’un soldat inconnu mais ma curiosité a été trop grande. J’ai appris qu’il s’agissait du soldat Henry Tannenbaum. Comme moi, il était de New York.

Un autre épisode similaire est arrivé plus tard durant la guerre. Le 28 février 1945, notre mission fut de capturer une ville allemande. Un tank ennemi s’est dirigé vers nous. Un GI l’a alors détruit avec son bazooka. La fumée sortait du blindé et un soldat allemand en feu en sorti. J’ai pris une photo de son corps. Une mitrailleuse nous a ensuite tiré dessus et j’ai plongé à terre pour éviter les balles. Le soldat allemand était près de moi. Je pouvais l’entendre dire son dernier mot: « Mutter » (mère en allemand). C’était vraiment touchant. Je pouvais sentir sa chair qui brûlait. Je l’ai inhalé. C’était l’odeur de la mort. Depuis ce jour, je ne suis plus le même.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Nous étions en Allemagne à Hohenlepte. Quelqu’un m’a réveillé pour me dire que la guerre était terminée. Croyez-moi ce fut le plus beau moment de ma vie. C’était vraiment incroyable. Nous venions de gagner la guerre. Je voulais aller dans les bois entendre les oiseaux chanter mais j’ai alors vu un cadavre dans un fossé. C’était une allemande richement vêtue. Elle avait avec un panzerfaust, un bazooka allemand, et un casque à ses côtés. Elle était soldat. Un couteau était planté dans son vagin. Un GI m’a raconté qu’elle avait été violée par 3 soldats en furie. J’ai jeté le couteau et j’ai mis une couverture sur cette femme. Mais en tant que photographe, je me suis interrogé sur la notion de témoin. J’étais là à cet instant et je devais montrer ce qui s’était passé. J’ai alors retiré la couverture et j’ai pris la photo de cette femme morte dans ce fossé. J’ai regretté plus tard. Ce fut la photo la plus affreuse que j’ai pu faire pendant la guerre. Je ne voulais plus entendre les oiseaux chanter. La guerre finie, j’en avais assez de la violence et de la mort. La photographie m’a immensément aidé car grâce à elle, j’ai toujours été bien occupé. Je n’avais pas le temps de me souvenir des horreurs de la guerre.

.

.

.

Est-ce impressionnant de prendre des photos de personnalités telles que le président John Fitzgerald Kennedy, Sophia Loren ou Ursula Andress?

.

.

.

.

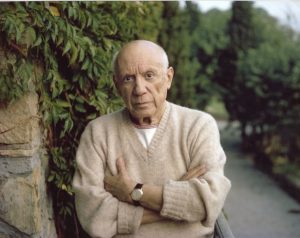

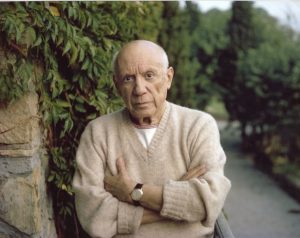

Il n’y a pas de différence entre les personnes. J’ai pris des photos de tout le monde et je n’ai jamais été intimidé par quiconque. Par exemple, j’ai passé deux jours avec le

grand Pablo Picasso mais je savais qu’il était autant humain que moi.

J’ai toujours essayé de rendre les filles et les femmes que j’aimais belles. Je n’utilisais pas d’effets. Uniquement de la lumière naturelle. À presque 100 ans, je continue à rechercher la beauté partout où elle se trouve. L’humanité a une beauté unique [M. Vaccaro tient son appareil photo]. J’ai acheté cet appareil à Wezlar (Allemagne) en 1954. J’étais déjà un photographe « célèbre ». L’Allemand, M. Lautz, qui a réalisé cet appareil, m’a dit : « C’est pour vous. Je vous le fais cadeau. » Depuis ce jour, je garde toujours avec moi cet appareil photo.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

https://www.amazon.fr/Entering-Germany-TONY-VACCARO/dp/3822859087

.

.

.

During the war, were you just a soldier holding a camera or you were also a photographer ?

.

.

.

.

I was first a soldier and a photographer. I had a camera and in every town we went through I could have films. The army even gave me films too. In Normandy, everything was destroyed. I couldn’t go off and

find some open shops. One day, I passed by the ruins of a photoshop. I went through the ruins and saw the chemicals. I put them together, I mixed like a gallon and warned them up with my finger. At night, I developped ten rolls in 4 army helmets.I dryed the films on branches of a tree. The only light was the moon. The next morning, I looked on the negative of the photos and it was perfect.

In 1945, I went to a photoshop in Belgium but I told them I didn’t have the money for the films. It was finally not a problem; the shopkeeper gave me the films but I promised to give them back someday. In 1995, I came back to Europe for several exhibitions. And because it was the 50th anniversary of V-E Day, I visited again the photoshop and I returned the 2 old films. 2 weeks ago, a belgian newspaper reported the story and the family who owned this photoshop contacted us.

.

.

.

Why did you use the name ‘Tony’ ?

.

.

.

.

My birthname is Michelantonio Celestino Onofrio Vaccaro. As a kid, people used to call me Mickey. When I was teenager, I was Tony (the abreviation of Michelantonio). When I went into the army, I became just Michael. The Americans didn’t like my Italian name then, without ceremony, they named me differently. When I worked for Look magazine, I used the name Michael A. Vaccaro. For Life magazine, I used Tony. But in the end, I have always been Tony.

.

.

.

.

What did the other soldiers think about the fact you were taking pictures of them ?

.

.

.

.

They were very grateful because I took pictures of them. In France or in Belgium, I used to go to camerashops and print the pictures on paper. It was great souvenirs for the other soldiers. They could send photos home. It was a proof for their family they were alive and well. Around January 15th 1945, during the Battle of the bulge, I was on leave and went to ‘La Wallonie’ newspaper offices that was almost abandonned. For about 10 days, I made new friends there and for the first time, I had the opportunity to store my photographs.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

During the Liberation, did you feel you were living some great moments with the French people ?

.

.

.

.

They were very happy to be indeed my models. The French used to kiss us and say « Merci », « C’est très bien ». Freeing them from the Germans was like a gift. Even a woman in Mont-Dol ran up to soldiers and gave her kid to one of us, Pfc Logfren. I took the photo of this moment. When a mother puts a kid to the arms of a stranger- it means she trusts more than anything else.

I am sure that woman couldn’t have done that with a German soldier. It is sad because Logfren was gone missing in the Battle of the bulge, months later. He probably get killed.

As a photographer, I knew I was doing something special. Normally, the army has always some people to take pictures but finally war photographers were not around. So I decided to cover all these moments we all lived. In WW1, there were not any photographers on the front line or in the towns nearby. During that time, the cameras were too heavy. There was no rule against it. When WW2 started, the US army didn’t even think about having cameras among the troops. In the 83rd Infantry Division, there were about only 15 cameras. Some soldiers had their own cameras too. However, the photos were not so good. I had learned to be a good photographer so I knew how to take a good picture. My war photos gave me the opportunity to work for journals such as Flair magazine and Look. When the Korean war started in 1950, the US army forbad cameras so I was lucky to be allowed to take photos during the war.

.

.

.

.

‘The kiss of liberation’ is your favorite picture. You describe it as human picture not a war picture. Why, after all these years, after all you have seen in your life, this photo is still magic ?

.

.

.

.

The moment was indeed incredible. It took place on August 14th 1944. We were celebrating the liberation of the town of Saint Briac. Girls were dancing around Sgt. Gene Costanzo (from Pittsburgh) and a little girl puts her scarf around the neck of the G.I. then kisses him. I ran across the place to take this photo. It was a tradition in Brittany to kiss three times. With only two kisses, I would have missed the picture.

General Eisenhower who later becomes President of the US wrote me a letter. He considers the photo as the greatest one of the war in Europe. Ike should have said WW2 but wanted to be respectful to Joe Rosenthal who took the photo of the GI’s raising the flag at Iwo Jima.

Even so many years after, when I came back to Saint Briac, I met the two sisters who were dancing in the back. It was so moving.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Did you speak with German prisoners ?

.

.

.

.

Speaking French and German, I could be useful sometimes. I interviewed some German prisoners.

One day in Normandy, one French speaking interpreter didn’t understand a farmer. I came over and heard some Molisean words. I come from Italy and grew up in the Molise region. So I understood what he was saying. This man was actually an Italian prisoner living in France. I said nothing to the officers because it could have given him some troubles.

.

.

.

.

Did you celebrate Christmas 1944 ?

.

.

.

.

Yes we did. It was during the Battle of the bulge. In the middle of the forest, on the front line, we decorated a Chritmas tree and I took a picture. Despite the bad times, we tried to have some fun together.

.

.

.

You also took photos of dead bodies. You think Death is a real character ?

.

.

.

.

I took indeed many pictures of dead americans and dead germans. I did it because I wanted to tell people that War is not a game. There is no good german, good french or good american, there are only human beings. During the Battle of the bulge, I was guarding the CP all night. It was really new for me because they used to have some big guys for this duty so they never used me. At 2 am, I heard some footsteps on the snow. I shouted : « Who’s there? » It was Sgt Harry E. Shoemaker (F company, 331st Infantry). I knew

something was wrong because a sergent could never leave his platoon. He was the only survivor and took me to the place of the combat. I saw all the dead bodies on the snowy field. The Germans killed all the soldiers with a machine gun and a Tiger tank knocked out all the American tanks around. It was desolation. Shoemaker told me he witnessed a German soldier, dressed in white, shot all the 27 GI’s bodies with a pistol. I saw a peaceful dead body covered in snow. I was like taking a requiem photograph. Although it is the ugliest aspect of life, in this picture, Death is beautiful. What a contradiction! When you are artist, you have to put your feelings aside. You must be a cold-blooded ‘son of a bitch’. Although I wanted to take a photo of an unknown soldier, my curiosity was too big. I found out that dead GI was Henry Tannenbaum from New York like me.

The same happened later during the war. On February 28th 1945, our mission was to take a German town. An enemy tank was moving toward us. A GI used a bazooka to knock it out. We could see smoke and a German soldier went out, burst into flames. Even on the ground, he was still on fire. Then I took a picture of the body. A machine gun hit the tank and I dove down. I was very close to the German soldier. I could hear his last word : ‘Mutter‘ (Mother in German). It was really touching. I smelled his burning flesh, I inhaled it. It was the smell of Death. Since that day, I have never been the same.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.Did you celebrate V.E. Day (May 8th 1945) ?

.

We were in Hohenlepte- Germany. Someone woke me up to tell me the war was over. Believe me I thought it was the most beautiful moment of my life. It was unbelievable. We had won the war. I wanted to go to the woods to hear the birds singing but I finally saw in a ditch the dead body of a wealthy dressed German woman. She had a panzerfaust and a helmet with her- She was actually a female soldier. A knife was stuck in her vagina. A GI told me she was raped by 3 angry soldiers. I threw away the , put a blanket on her. But as a photographer, I asked myself was kind of witness I was knife. I was here to report reality. So I removed the blanked and took a picture of this dead woman. I regretted to take it. It was the ugliest picture of the war. I didn’t want to hear the birds singing anymore. With the war over, I have had enough of violence and death. Photography helped me tremendously because I was always on the move. I had no time to remember the horrors of the war.

.

.

.

.

Is it impressive to take pictures of characters such as President Kennedy, Pablo Picasso, Sophia Loren or Ursula Andress ?

.

.

.

.

There is no difference between people. I took pictures of everybody and I have never been intimadated by anyone. For instance, I spent at least two days with the great Pablo Picasso but I knew he was human just like me.

I always tried to make girls and women that I liked beautiful. I didn’t use special effects only natural lights. At almost 100, I still search for beauty everywhere. Humanity has a unique beauty. [M. Tony holds his camera] I bought this one in Wetzlar (Germany) in 1954. I was already a ‘famous’ photographer. The german, M. Lautz, who made this camera told me : ‘This is for you’. It was his gift to me. Since that day, I have always kept this camera with me.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Further reading :

Official site : http://tonyvaccaro.studio

Book : « Entering Germany 1944-1949 » Taschen 2001 https://www.amazon.com/Entering-Germany-1944-1949-Hardcover-2001/dp/B010EWHGFU

Instagram : https://www.instagram.com/tonyvaccarophotographer/?hl=fr

All the work by Tony Vaccaro as Tony Vaccaro / Tony Vaccaro Studio